Before you start to use the Squonk computational Notebook its useful to understand a number of key concepts.

Notebook

A Notebook is the core component you work with. You create a notebook to handle a particular workflow. A notebook can be private to you, or it can be shared. Currently the only sharing possible is to make the notebook public so that all users can see it. But we will be adding fine grain sharing where you can control who you share with and what they can do with your notebook.

A notebook has a small number of basic properties, such as name, description, owner and sharing status.

Notebook Editable

The version of the notebook that you work on and edit is termed a Notebook Editable. This includes the contents of the Canvas (the Cells). As you modify the canvas (e.g. move the position of a cell) the definition is automatically saved. Editables belong to you, and only you can edit them.

Canvas

The Canvas is the area of the Notebook Editable that you work with and manipulate, primarily by adding Cells to it and by connecting the Cells.

Notebook Savepoint

When you are ready with your Notebook Editable you can click the save button to create a Notebook Savepoint. This Savepoint is a snapshot of the current notebook contents and the values of its Variables (the Cell outputs). The Savepoint is created based on the current Editable, and then a new Editable is created that you can continue to work on.

You can create multiple Savepoints reflecting your history of work.

You can go back to a Savepoint and start working on it. When you do this you are creating a new Editable that you work with, ahd most likely you will have created a branch in your workflow (e.g. to try out two different methodologies).

Savepoints are visible to all users whom you have shared the notebook with, allowing them to use the work from that Savepoint. When doing so they will create a new Editable from the Savepoint that they can work with. Savepoints themselves are not editable so that they provide a “frozen in time” snapshot of that version of the notebook (actually, strictly speaking their descriptions can be updated, but not their contents).

All the Savepoints and your Editables for a Notebook are shown in the History panel.

Cell

Cells are the key components you work with on a Notebook Editable. You add cells to an Editable by dragging from the Palette to the Canvas. To see what cells currently exist look in the Cell Directory.

Cells usually have inputs and outputs, often both, though some cells, such as text or HTML cells do not have inputs or outputs. These inputs and outputs are Notebook Variables.

Most Cells have Options that can be set (either directly in the Cell UI or using the advanced options dialog) that determine the execution of the Cell. During execution the input Variable(s) are read, the operation of the Cell performed according to the specified Options, and the output Variable(s) written.

Some Options are defined by user interaction. For instance, in various of the visual cells you can select a set of records (e.g. by dragging out a region in the Scatter Plot cell), and this Selection is represented as an Option. The Selection Option can be propagated to other cells where it can act as a Filter, facilitating dynamic exploration of data.

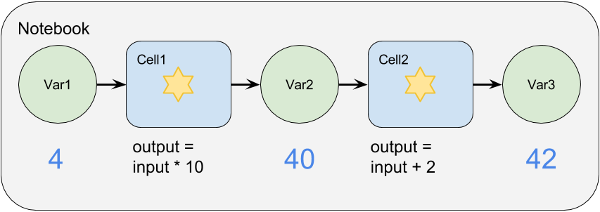

The following diagram illustrates the cell execution process. The Notebook has two cells on it, with the output of Cell1 being the input of Cell2. Both Cells perform simple mathematical operations. When the first cell is executed its input variable (4) is read and it generates its output variable (40). When Cell2 is executed it reads that variable and generates its output variable (42).

This example is over-simplistic as real variables are usually more complex than simple numbers, and cells can have multiple inputs and outputs.

Variable

As just mentioned, an input Variable is read and an output Variable is written during Cell execution. These Variables can be thought of as programming variables that is read or written during execution of the Cell. In a simple case a Variable could just be a simple value such as an Integer or a String, but often they are large arrays of objects that are to be handled as a stream of data e.g. a stream of molecules, each one of which is processed by the Cell. One of the most important types of Variable is a Dataset.

It’s important to understand that a Variable is written by a single producer Cell, but can be read by multiple consumer Cells.

This ability to handle large and complex variable types is one of the core strengths of the Squonk Computational Notebook.

Dataset

A Dataset is a particular type of Variable that represents a stream of objects of the same type, with those objects having properties. Many Cell types read and write Datasets. The dataset contains metadata that describes the objects and their properties. We’ll take as an example the need to process a set of molecules that might be read in from a SD file. The SDF Upload Cell allows to upload the SD File, and when you execute it the Cell generates a Dataset of molecules, one molecule for each record in the SD file. The SD file properties become properties of the molecules. The metadata describes the types of values (in this case they will all be String values). This dataset is then saved as the notebook Variable that is the output of the SDF Upload cell. This Variable can then be read by a downstream cell, possibly one that calculates properties from the molecules.

A dataset has 2 components:

The results

These should be thought of as a series (or stream) of “records”. Each record has “properties”, with a property being identified by a name and a value for that particular record. For instance records can have a property named “colour” which can have values like “red”, “green” or “blue”

Metadata about the dataset and its results

The metadata allows the dataset to be described, as well as its properties. This is a key feature of the Squonk Computational Notebook as it allows a datasets to become self-describing allowing string traceability and reproducibility. For instance the history of the dataset and its properties is recorded so that by looking at the metadata you can find out where particular properties originated from and what had happened to them during processing.

The best way to see the results and metadarta is to use the Results Viewer that allows the output of each cell to be viewed.

Dataset of Molecules

More specifically known as a MoleculeObject Dataset, this is a specialised Dataset designed for molecules. Each MoleculeObject has 2 integral properties, the source which defines the structure in some know textual format, and that format is specified by a format property. An addition arbitrary properties and metadata can be defined for each MoleculeObject as with any type of dataset, and all is convertible to and from JSON for persistence and exchange across the network

As an example. let’s look at benzene, and let’s assume we have calculated its LogP using RDKit. Its JSON representation could be:

{"uuid":"f664c6c1-5295-4874-a85c-152966baddb2","source":"C1=CC=CC=C1","format":"smiles","values":{"LogP_RDKit":1.6866}}

Let’s look at this bit by bit:

- uuid is a unique ID of the MoleculeObject. Automatically generated and used primarily for internal purposes

- source is the source of the molecule, in this case as a smiles string, but molfile format would also be possible

- format is smiles. Alternatively it could be mol for molfile format.

- values are a map of properties for the molecule, in this case a single property named LogP_RDKit with a value of 1.6866

A key aspect of this is that the source of the molecules is held in a toolkit neutral manner, allowing inter-operability between different toolkits. Anything that can interpret a smiles string could handle this. Similarly for molfile.A dataset of these would contain an array of these MoleculeObjects, as well as metadata that describes the properties (e.g. that the LogP_RDKit property is a floating point number) and any other properties of the dataset as a whole.

The MoleculeObject stores the structure source in some text format (e.g. smiles), but it is up to the chemical toolkit implementations to parse that structure (e.g. smiles string) and interpret it correctly. We make no attempt to verify that the specified structure is valid. If it is not the toolkits will complain when they are asked to work with the molecule. The vast majority of structures supplied are valid, but a small fraction may not be, and some toolkits may have bugs or quirks that prevent it being handled correctly. If this a concern you can verify that all the molecules are valid (or filter out ones that are not) for a particular toolkit using a cell like the Verify Structure (RDKit) cell.